Every now again in the history of the theatre, surprising artifacts emerge that help us to better understand the theatre’s past. These artifacts take many forms and when put together, resolve into increasingly clearer pictures of what theatre practitioners did and how they did it. Knowledge of the theatre’s past can greatly enhance the work of modern theatre artists as well as the audience’s experience of the performance. The superimposition of past or even ancient practices on modern theatrical productions creates the opportunity for insight into what the theatre is and always has been in terms of its power as a transmitter of values, beliefs, and culture. When done well, performances of this nature allow audiences not only to be transported to the world of the play, but also to inhabit the zeitgeist of the world in which the play originally appeared.

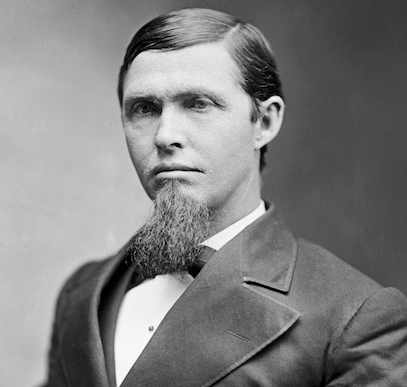

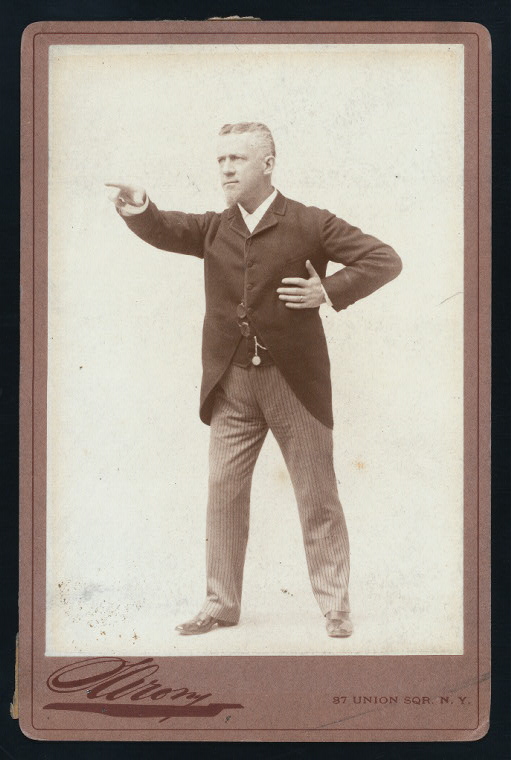

The Senator, first performed in 1890, is such an artifact, the text for which was discovered by historian Johanna Wickman in the course of her research on Kansas Senator Preston B. Plumb. Lost for over a century, The Senator was a success in its time, produced on Broadway and later on national tours, both of which starred the famous American actor, William H. Crane, in the role of Senator Hannibal Rivers. Crane modeled his performance on his study and observations of Plumb, and it was received as an homage to a uniquely dynamic persona who embodied the vigor, optimism, and boldness of America in the late 19th century.

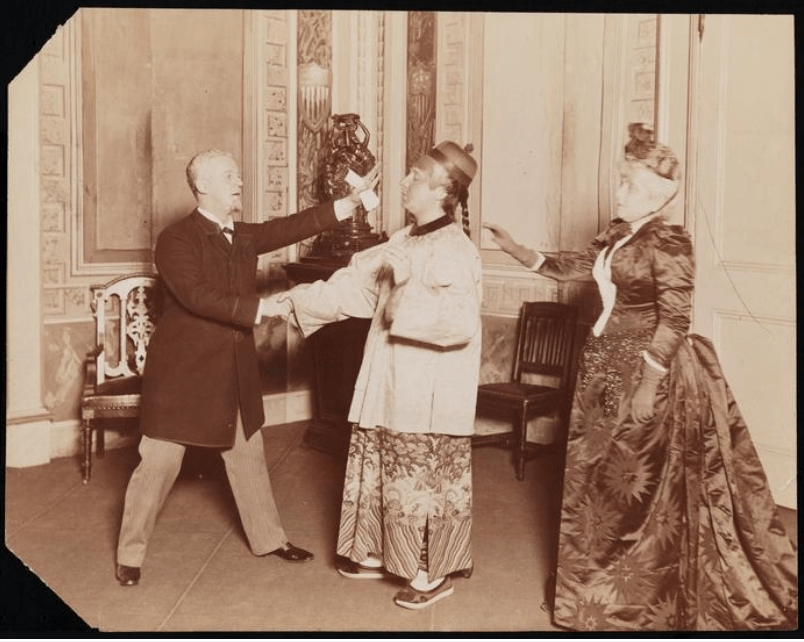

David D. Lloyd’s and Sydney Rosenfeld’s play was wrought in the form of the melodrama, widely popular in both the United States and Europe. The characteristics of the melodrama are deeply embedded in our collective psyche: handsome heroes and comely heroines, often not as helpless as they seem, save each other and the day; villainous dastards and their unscrupulous henchmen are exposed and punished as they deserve; lively girls and comedic sidekicks provide commentary and additional intrigue; haughty dowagers flaunt their wealth; “the virtuous poor” toils on; and what were known in the industry as “stage ethnics” of every kind caper about the stage as the outliers for whom the American dream was not, for the most part, unattainable. Often these representations were based on stereotypes of the ethnic group’s speech, physical appearance, dress, religion, culture, and accent—a theatrical practice that can trace its pedigree to the theatre’s ancient Greek founders themselves. Seen from a modern perspective, such representations can be reasonably understood as reductive, misleading, and offensive, and as having no place on our stage today. However, if we can regard the theatre as a window into history, we realize that the representation of stage ethnics tells us much more about the people who created those representations than about those represented.

In the script for The Senator, representation of various stage ethnics (German, White Southerner, Chinese, and Black) are indicated. The representations range from innocuous to unacceptable in any context. As our project is to reproduce The Senator as it would have been experienced by a 19th century audience, this creates a conundrum. We were forced to make revisions to both the script and presentation of the play in such a way as to do no violence to the play, nor to modern sensibilities. Thus the most objectionable material has been cut completely, while we have preserved within the boundaries of good taste the representations that are respectful of the groups represented, in a manner more or less consistent with the acting conventions of the time.

This production of The Senator has been a singular opportunity for all who worked on the project to conflate the history of the American West with the history of theatre. In the very community whose ancestors were served by Senator Plumb, local theatre artists and scholars have joined together to create a once-in-a-generation experience of a lost play, and of a time lost. Our collaboration has been fascinating, lively, and replete with a generosity of spirit and resources without which the production would not have been possible. It is with gratitude that we acknowledge the contributions of our collaborators, Fort Caspar Museum Association, Stage III Community Theatre, Casper Children’s Theatre, Opera Wyoming, the Natrona County School District, and the City of Casper Joint Powers Board. It is our hope that The Senator project heralds a new era in Casper of mutual support and cooperation among the many arts organizations that grace our city and the government agencies at all levels capable of assisting in whatever ways they can.

William Conte

Artistic Director

Theatre of the Poor