Translating and Staging the Menaechmi by Plautus

We conclude our “Found in Translation” season with one of the great comic masterpieces from antiquity. Written by Plautus early in the 2nd century BC, Menaechmi was presented for the first time in the context of the festival games, or ludi, of Republican Rome. These were spectacles of enormous scale, staged in temporary amphitheaters lavishly decorated to house celebrations of military victories, religious holidays, and even the funerals of private citizens. The Games featured a wide variety of spectacle entertainments of which the presentation of plays was a usual feature.

Inspired by our fascination with theatre history, we are staging Menaechmi in a style consistent with that of the ancient Roman theatre. We chose the Washington Park Band Shell in Casper, Wyoming because its construction is vaguely reminiscent of the stages of antiquity—a semi-circular space at the ground level, with steps leading to a middle tier, and another flight leading to the main stage level. The entire structure including the domed shell above the stage is made of concrete; though it has been well maintained since it was built in the 1930s, it is also well weathered and in its presence, one gets the sense of a time long past. Locating Menaechmi on this site continues our commitment to producing work in found spaces that enhance the experience of the play by facilitating a total fusion of venue and content.

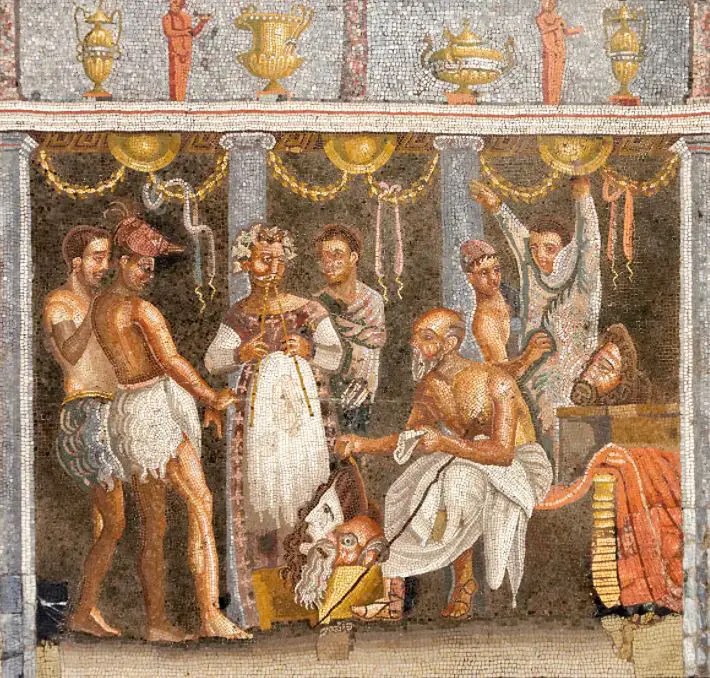

The actors in our production wear the Greek-style costumes that would have been worn by the original Roman actors, as Plautus drew the plot from an earlier 4th century comedy by the Greek dramatist Menander. Like their Greek predecessors, the Roman actors wore masks that signified their characters’ types, and our actors do so as well. The masks were thought to embody the essence of the character, or persona, all of whom had distinct physical and psychological traits that were familiar to the audience. Once donned and imbued by the actors, the masks become animated despite being static representations of greed, wrath, lust, innocence, cunning, etc. The audience enters an uncanny valley populated by ancient archetypes whose unchanging nature is inscribed on the masks, which make the actors seem like marionettes or living dolls that exist outside of time, and are therefore universal and eternal. We believe that this was largely the effect achieved in the ancient theatre and one we hope to reproduce for our audience.

Translating the play from the original Latin offered unique insights into ancient theatre, as well as the mindset of the Romans. The Latin original was in verse and would have been mostly sung or chanted; our translation is rendered in blank verse and though it will not be sung, the speeches are accompanied by music as they were back then. The Romans delighted in complex, sometimes convoluted sentence structures rife with puns, allusions, circumlocutions, evasions, negations, and seemingly endless layers of subordination. We have attempted to convey this playful complexity by hewing closely to the structure and syntax of the Latin original, and heightening the language by means of an elevated, overly formal diction which we hope will have the proper comic effect. We have also attempted to preserve the “earthiness” of Plautus’s language by interpolating when necessary modern slang terms equivalent to the Latin original; we do nothing to inhibit the occasional bawdiness and crude humor that has been a hallmark of comedy since, well, since Plautus, and the Greek comic genius Aristophanes, who preceeded him. The experience of translating the play allowed us to touch the mind of Plautus, to experience his thoughts directly, and thereby understand his intentions more precisely. For the Latin text contains no stage directions; we had to infer blocking and business based on what his characters are saying. What the translation process revealed was Plautus’s sophisticated understanding of the art of the theatre as something different from the art of writing plays. Plautus knew that “funny” isn’t so much what an actor says, but what an actor does, and that theatre is most fun when it’s having fun, and making fun, not only of the Greco-Roman world, but of itself as well (in modern theatrical theory this is known as metatheatricality, and in art generally, self-referentiality).

In staging the play we decided to run with this aspect of the comedy. The jokes, bits, and schtick that Plautus incorporates are familiar to us today because they are transcendentally funny; we have seen them a million times, repackaged and re-presented to suit the times, but always fundamentally the same. Examples of this are Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors, Goldoni’s The Venetian Twins, and the Rodgers and Hart musical from the 1930s, The Boys from Syracuse, all reworkings of the Menaechmi of Plautus, who himself appropriated plots and ideas from the Greek “New Comedy” of the 4th century BC, almost all of which are lost save for fragments of various length. And let us not forget the brilliant Golden Age musical, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, in which various tropes and elements from the plays of Plautus are stitched together in a way that made both Plautus and his comedy immediately accessible to audiences of the early 1960s, as well as today. Our production is rooted in this history and blooms under the sunshine of our predecessors.

If Tragedy is humanity suffering beautifully, Comedy is humanity suffering stupidly. Our last outing, Miss Julie, illustrates the former, whereas our production of Menaechmi illustrates the latter. It is our intent that this production brings to the audience the fullest possible experience of the ancient Roman comedy, short of building a time machine and traveling back to see it for oneself. Our troupe of actors performs in the spirit of the Grex, the Latin word for “flock” but also an acting company. Our lives entwined by our commitment to the work, under the leadership of a Dominus Gregis (literally, “the master of the flock”), the Grex of the Theatre of the Poor flows from show to show, venue to venue, in search of the secrets that produce unforgetable, transformative performances of the best plays ever written. As our season comes to a close, we thank all of you who supported us, cheered us on, donated time, talent, and a buck or two, and encouraged us with your enthusiastic reception of our work. It continues because you believe in us, and we believe in what we do. Once again, our thanks, and we look forward to seeing you during our 2023-24 season, The Miseducation of the American Mind.

William Conte, Ph.D

Artistic Director