Our “Year of the Phoenix” begins! The plays of this season circulate around the idea of new beginnings; as the phoenix rises from the ashes, so do the protagonists of this slate of dramas “die” to their old selves and are “reborn” as something else. We hope you will join us for each production as we explore this idea from different perspectives, and continue to produce the best of what has been thought and written for the theatre.

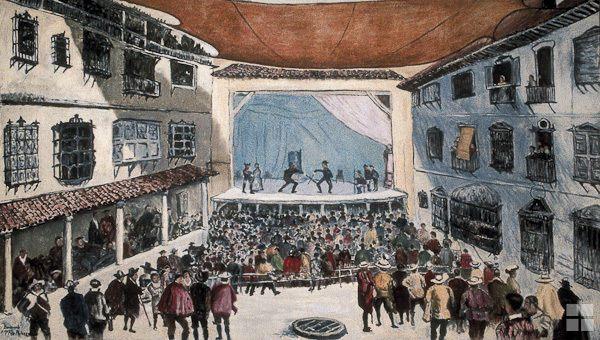

Born in 1600, sixteen years before the death of his near-contemporary William Shakespeare, Calderon de la Barca stands as one of the world’s greatest dramatists. The Spanish Golden Age (el siglo de oro), was a period of great theatrical fecundity from which emerged a unique literary style. Called comedias, these plays were often written in three acts, with content drawn from Spanish history, Christian theology, medieval allegory, and the “low culture” of the peasant class, which often proves to be wise and insightul. The theme of honor runs through these plays with a persistence bordering on obsession. Easily lost, painfully restored, and the source of nearly impossible to resolve complications, honor drives the characters and the plot, and upon inspection one can plainly see elements of the melodrama of the nineteenth century. The comedias are also characterized by passionate speeches of considerable length, often as contemplative and profound as anything found in their British and French counterparts; yet, all this is contrasted by a playfulness that endows the plays with an sense of unreality, such as is found in fairytales.

This season, the Theatre of the Poor returns to its roots in the environment: found spaces, parks, and public places such as the sundial sculpture at the corner of S. Beech and W. Collins St. This sculpture, entitled the Confluence of Time and Place, is a masterpiece of conception and execution. It is perfect for our production of Life is a Dream. The sundial itself represents the mountain to which our protagonist is chained; the functional sundial is part of a schema comprising the nearby greenspace, with stone bollards marking the hours, and is constructed in such as a way as to create a correspondence between our immediate “local” time, and the passing of time across geological epochs as can be seen in canyons and valleys across Wyoming. Although the sculpture is “about” time and place, it transcends both by means of its iconic presence and stillness. Like a fairytale, in the presence of the sculpture we are nowhere in particular at no particular time, which places us squarely in the realm of the imagination, and which also provides a catalyst for the unique mise-en-scene we have invented for the production.

Life is a Dream does not disguise its overarching theme: the title says it all. The protagonist Segismundo is an existential Everyman who is punished for the crime of existing. His father, the philosopher-king Basilio, has read the boy’s catastrophic future in the stars and resolves to prevent his son from wrecking horror on his kingdom, Poland. The crux of the play is whether the verdict of fate is irreversible, or whether human beings can intervene against fate and change it for themselves and others. Alongside these musings runs an adjacent plot involving the dishonored Rosaura, who disguised as a man is on a quest for revenge on Astolfo, the Russian duke who defiled and abandoned her, and is now scheming to marry the king’s niece Estrella. We discover through the standard “token of recognition” that Rosaura is really the daughter of the king’s henchman Clotaldo, which complicates matters for him, as he is torn between his loyalty to the throne and his obligation to restore his daughter’s honor. It is clear that Calderon was well aware of his audience’s affinity for complex plots and characters tormented by impossible conundrums, which Life is a Dream provides in abundance.

Aside from its anticipation of the melodrama, Life is a Dream is among the first theatrical meditations on what we now call “simulation theory”: the idea that none of what we experience is really real; that it is all manufactured for us in “the matrix”; that illusions can be quite tangible and what is tangible, merely illusion; in short, that life is a dream. In simulation theory, we are the product of the imagination of an alien super-intelligence. Our production is being staged as the product of the imaginations of four siblings at play, “projected” from their minds onto the performance site. It is contrived so that the characters seem to exist and act under the control of the children, whose “dream” is the play we are watching. In this way we frame the play’s philosophical discursions and melodramatic intrigues within the simplicity of children’s fantasies, while advancing the storybook quality that makes the play accessible to all.

The idea to bulild the show around children did not come to us until late in the process. The siblings are members of the TotP KIDS workshop, which is free to the public thanks to an Arts Learning Grant from the Wyoming Arts Council. In need of a mob, we attempted to recruit extras, but only these four kids were available. As we rehearsed, we realized that the presence of the kids amplified the play’s sense of wonder, that this was somehow “working,” but no one could explain exactly why. The leap to the present conception of the play was sudden, and as we spanned the gap created by the uncertainty of what we were doing, we arrived at a vision that brings all the elements together in a mise-en-scene that is singular in its uniqueness.

Or maybe it’s just singular in its convolution. With high theory, one always runs the risk of putting hats on horses, or worse, “pouring from the null into the void,” as Gurdjeff puts it. A director’s cleverness should never occlude a playwright’s brilliance, and, if so charged, we plead “no contest.” As always we thank you for your support of the Grex.

William Conte, Artistic Director