The Historical Context

From the 1830s to the 1870s, when melodrama was the preponderate dramatic form in America and Europe, theatre was the primary source of public entertainment for most people most of the time. The working and middle class audiences saw their own aspirations mirrored on stage: right conduct and hard work were rewarded, vice and turpitude were punished, and justice always prevailed. There were villains and heroes and character types of all sorts; actors of the period specialized in the portrayal of these types, known as their “lines of business.” The acting style was based on “personation,” developed in Renaissance England as a way of presenting the movement, appearance, mannerisms, and speech of different classes and kinds of people. The characters were easily recognizable and actors knew what audiences expected, so they tended to construct their performances on a framework of stereotype and convention. The overwrought plots of the melodrama were often driven by an evildoer’s cartoonish cruelty and resolved with implausible fortuity; combined with “sensation scenes” such as burning tenements, bank riots, horseback chases, and the classic rescue from an oncoming train, the melodrama evolved from entertainment to cultural icon. Durable as weeds and with a pedigree reaching back to Euripides, the tropes of melodrama abide today in innumerable plays, films, and TV shows, especially soap operas, and they will endure in our theatre so long as they remain lucrative.

And Then Came Ibsen

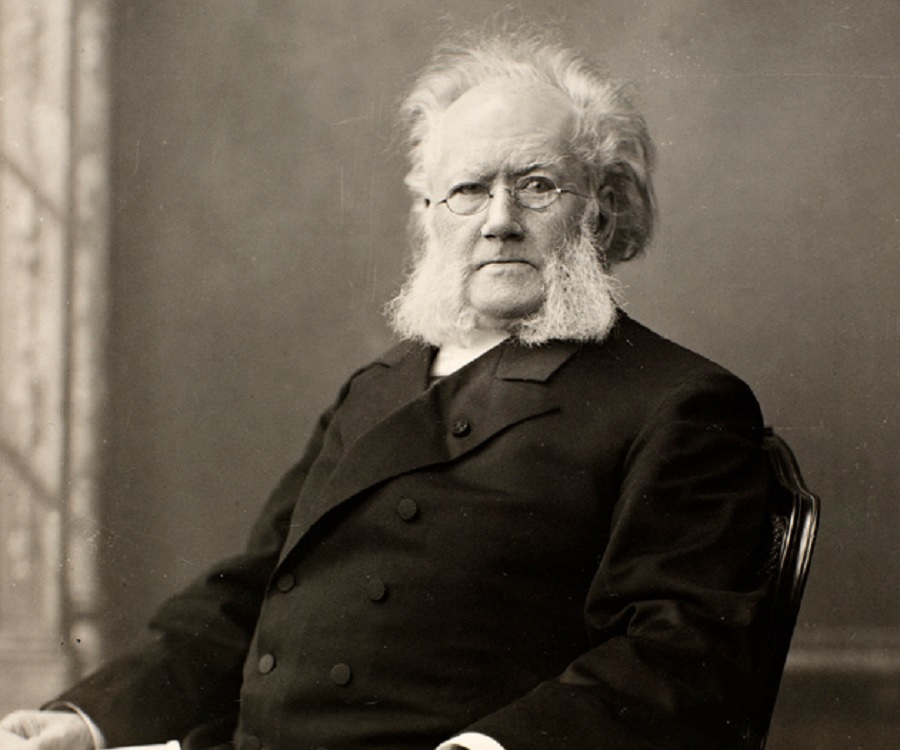

Henrik Ibsen is universally acknowledged as a literary and dramatic genius, the Father of the Modern Theatre. No playwright since Shakespeare had had such influence, such ability to elevate what had been mostly craft into the highest art. The early phase of his career was marked by poetic dramas that drew from Scandinavian myth and legend, most notably Brand and Peer Gynt. By the 1860s, when Romanticism began to wane, Ibsen came under the influence of Naturalism, a literary movement first developed in the novels of author/philosophers such as Emile Zola. The Naturalists were convinced that literature should aspire to as objective a representation of the world as possible. On stage, this conviction was expressed by means of sets so realistic, it seemed as if a wall had been removed, and the audience was peering voyeuristically into someone’s home, or into a tenement, factory, butcher shop, as the play required. Social issues such as the rights of women and workers, the problems of crime and vice, were explored through the “scientific” lenses of psychology, heredity, and the historical struggles among economic classes throughout history. For Ibsen and his followers, “the past is present” at all times, with characters facing the challenge of having to overcome whatever was creating problems not only for themselves, but for the world at large. Ibsen showed how such characters should and could be imbued with the psychological complexity of real people, whose motives are often murky even to themselves. The black and white theodicy of the melodrama was replaced by an examination of a world of three dimensional human beings, a world in which justice does not always prevail, and where the possibility of failure and heartbreak was always looming. “No happy endings, no learning,” the credo of the showrunners of the hit comedy Seinfeld, was invented by Ibsen.

The Door Slams

When A Doll’s House premiered in Copenhagen at the Royal Danish Theater in 1879, it appeared at first blush to be just another melodrama. The happy home life of a successful bank manager and his beautiful wife is jeopardized by an unscrupulous villain who blackmails the heroine by threatening to expose her terrible secret. As per the form, audiences and critics expected the play to end with the rescue of the heroine, the vindication of her hero/husband, and the just punishment of the villain. Genius, however, does not bend to expectation. The hero turns out to be a coward, his “comic side kick” is a morose companion dying of syphilis, the villain is actually a decent man brought low by circumstances, and the heroine ends up having to save herself by means of an act so shocking, the audience did not know how to react. Nora’s abandonment of her family was an act of maternal indecency not seen since Medea murdered her sons to spite Jason. The door slammed. The play ended. The audience was stunned. The final moment is regarded by historians in sum as the loudest sound that had yet been heard in the theater.

The Aftermath

Not unexpectedly, A Doll’s House and subsequent plays by Ibsen caused controversy throughout Europe. Nora’s self-emancipation anticipated the modernism of the twentieth century, which at the time was inchoate in suffragism, Marxism, Darwinism, and psychoanalysis. Connoisseurs of theatre, actors, visionary theatrical managers, and critics such as George Bernard Shaw had realized that something powerful had come to the theatre, and that because of it, the theatre would never again be the same. To play characters of such depth and complexity, actors had to adapt to a new approach to acting, which Stanislavsky realized after “personation” made naturalistic plays seem ridiculous. Actors needed to be trained in a new “method” that would enable them to inhabit the imaginary circumstances of the play, allow the imaginary circumstances to inhabit them, and to perform with such authenticity, the audience forgets they are watching a play. With the advent of the twentieth century, an increasing vogue for Ibsen and naturalism inspired the establishment of subscriber-based, “independent” theaters in Europe as well as the United States. These smaller venues were unconstrained by the need to make profits from the big budget, spectacle driven entertainments of the Theatrical Syndicate; the experimentation fostered by what became known as “the Little Theatre Movement” allowed new voices to emerge and new visions to be revealed on stage.

Our Production

In point of fact there isn’t much to say about our production, other than that we have invested a great deal of energy into bringing the acting to the level of emotional authenticity and psychological realism that the script demands. We did what we could in creating a “habitat” for the affluent Helmers with the resources available to a “poor theatre.” It would be lovely if we had the means to reproduce the set exactly as Ibsen describes, including a functioning wood burning stove and a playable piano. But even if the set were the best that money could buy, it would be nothing without great acting standing on a platform of great writing. The talents of the TotP Grex are on full display in this production; we could not be more proud of the commitment and intensity they are bringing to the stage, on which depends the realization of the full power of the play. Ibsen leaves the question whether the play ends in tragedy or triumph to the audience, whom he trusts to contemplate what he has revealed about humanity long after we have exited the theater. As always, we thank the Wyoming Arts Council, our donors, and you our audience for your support not only for our work, but for all the arts in Casper, Wyoming.